What Am I Reading: Dungeon & Dragons Player’s Handbook, 5th

edition

Part One: Making History!

The

Dungeon Master looked up from his notes and pushed his glasses further up his

nose. “The tunnel finally ends in a huge cavern - you can’t see very far. But

before the entrance to the cavern there is a crack in the ground making a huge

hole blocking your way."

“How

far is the gap?” A player says.

“About

thirty feet - you can’t jump it.” The player checks his character sheet.

Another

player asks, “I look above the gap to the ceiling, what do I see?”

“Several

bleached white dangling roots - some are thick as tree trunks, some as thick as

a person’s arm, some very thin.”

“Are

they within reach?”

“No,

you’d have to jump.”

“Can I

make a running jump and use the vines to swing to the other side? I promise not

to yell like Tarzan.”

“Roll

...”

This

blog started off as a simple review of the new Dungeons & Dragons Player’s Handbook (Fifth Edition), but most

of the changes made in this edition required an explanation of what went on

before. The review turned into a history of the game itself.

Like

the archaeological City of Troy ,

the information at the top of the site was built upon a lower city with its own

information. This was built on the city before that, which was built on the

city before that.

To

explain the good and bad of Dungeons

& Dragons Player’s Handbook (Fifth Edition) and to really appreciate or

discredit what they had done, I had to dig into the treasure and trash of its

past incarnations.

It

started with miniature gaming - those fellows (let’s face it, miniature gaming

- especially in the 1960s and 70s - was a y-chromosome activity) who would lay

out model train terrain on a huge table or piece of plywood in a garage or

basement and place small-scale soldiers in Napoleonic or Civil War gear and

equipment, take out their tape measures and rulebooks and become omniscient

generals of historic battles.

Sometimes

the gamers would take medieval troops or earlier-era figures for their

miniature battles. Instead of Waterloo

or Gettysburg , they would re-enact

Bosworth Fields or the Battle of Alesia.

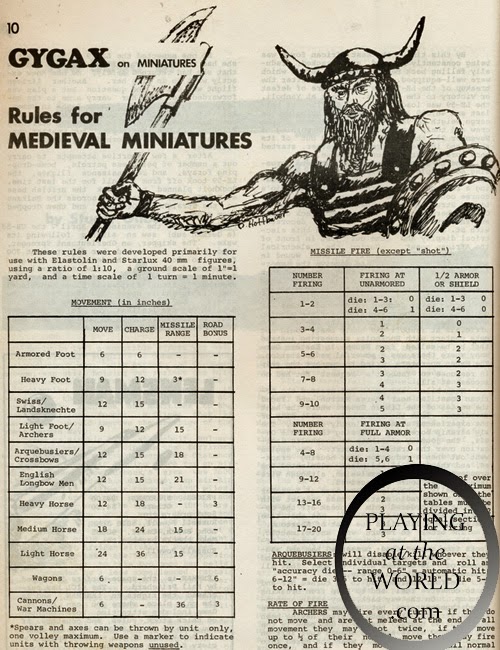

Rulebooks

for these types of game were plentiful. One such rulebook published in 1971 was

called Chainmail by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perrin. It did well.

The

authors wanted to have some fun and added fantasy elements to their medieval

miniatures. Instead of Charlemagne and his troops, elven soldiers took the

fields. Wizards blasting bolts of fire took the place of ballista. Dragons flew

overhead instead of boulders. Rules for such magical beings were informally

written out.

But

what if the gamers wanted to storm the keep? What if they wanted to go after

that dragon in his lair - deep within the bowels of the earth? Mass miniature

battles were joined by individual characters exploring caves and castles. More

rules were to help move groups of individuals instead of a mass of armies.

Sometimes the gamers played the individual characters while the miniature

figurines and terrain stayed in their cases.

The

individual rules took on new type of game and required a new game system. Gygax

and friends called it Dungeons and Dragons (“D&D”). D&D had simple

rules that were easy to follow. With some dice, a piece of paper and a pencil,

you could imagine playing a Lord-of-the-Rings elf or wizard (called a

magic-user) or a Conan-esque or Fahfrd-and-The-Grey-Mouser-like fighter or

thief. You could wander castles and its dungeons or deep into the bowels of the

earth to root out a dragon’s lair. You could use miniatures, true, but you

could do without them as well!

Your

character was based on the following attributes - basic physical and mental

abilities - strength, intelligence, wisdom, dexterity, constitution and

charisma. You rolled three dice and the total was your level of that attribute

- 3-18. The higher the roll, the better the attribute. Fighters needed high

strength, Magic Users, not so much - they needed a higher intelligence to cast

their spells. Thieves? Dexterity.

And to

add to the Tolkien flavor you could also become an elf or a dwarf. If you

played a human you chose which class you wanted to play - the aforesaid

fighter, magic user, thief, cleric (a holy healer/ fighter - think Knights

Templar). Elves and dwarves had no classes - you either played an elf or a

dwarf.

In 1977

or so, Advanced Dungeons and Dragons (AD&D) debuted. It was had new rules

and changed bits of the original. It wasn’t a different, improved edition to

the original. In fact for a time it was its own game. But it expanded the

basics: any race (elves, human, dwarves, halfling - non-copyrightable hobbits -

half-orcs, gnomes) could be any class they wanted with some limitations. Elves

can be fighters and magic users now. Dwarves can’t be magic users or clerics,

though. They can be thieves! Anyone can be a thief. AD&D had its own Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide and book upon book of

extra rules, stats on monsters and other characters one might meet in their

imaginative play. It added monks for the ninja-wannabes, rangers for the

Strider-ites, and bards so one can be a wandering minstrel, I ...

This is

about where I came in. I learned of D&D and AD&D through, of all

places, church camp. I learned the basics without actually playing the game.

That came in 1981 when our high school science teacher started a Dungeon &

Dragons club. There I played the game for the first time - a human wizard named

Mylock. The group even made the yearbook!

The game

was still basic and had lots of role-play. Theater of the mind, so to speak.

But the dice were still important. Let’s go back to the opening paragraphs.

“...

your Dex,” says the DM (meaning roll the dice and if it is less than your

Dexterity score you can, indeed, swing across on a vine)”.

{Roll}

“Made it!” says the player.

“I

throw a rope across to him,” another player says, “and tie it to the Magic

User. You’re next.”

The

player playing the Wizard rolls. He has a low Dexterity and the odds of him

rolling below that number is smaller than the others. “Missed it!”

“You

fall into the chasm, but you are tied to a rope and splat against the wall for

{roll} 2 hit points (you also roll a certain amount of “hit points” - this is

how healthy you are and how much damage you can take before your imaginary

character dies. Magic Users don’t have a lot of hit points - fighters do to

help them survive all those sword fights).

“I pull

him up,” says the first player.

“Make a

strength roll,” the Dungeon Master says. (Note: the Dungeon Master - DM - is

the person who oversees the players, sets up the scenarios, arbitrates the

rules, etc.).

{Roll}

“Argh! I have a 17 Strength and rolled an 18!”

“Those

are the breaks - the Magic User dangles above the abyss! But no other harm

comes to him.”

“Get me outta here!” shouts the Magic User.

“Get me outta here!” shouts the Magic User.

“I

swing across,” the second player says. He also has a high dexterity and is not

too worried about his odds. “Made it. I help pull up the Magic User.”

“With

both of you working together, you don’t have to roll Strength, the Magic User

is out of the crack and standing beside you.”

The

first player says, “I throw the rope across the chasm - let’s get everyone else

across before something bad spots us.”

“Too

late for that ...” mumbles the DM to himself, who rattles his dice and smiles.

TO BE CONTI NUED...

Copyright 2014 Michael

Curry

No comments:

Post a Comment